Aaaand we are back with our first post of 2025! It has been a difficult start to the year, with the wildfires in LA which have been and continue to be devastating for so many people. Before we go any further in this post, we want to share some resources for those affected by the Palisades and/or Eaton fires or those who want to help those who have been affected. We are so heartbroken for those who have lost homes, pets, loved ones, livelihoods, or even just a sense of normalcy and safety. These experiences are close to home for us personally, and from that we know that the best way to get through this is with time, and in community.

When we started this newsletter, our goal was to provide some hope and actionable information for ourselves and anyone interested in reading along. This is still our goal but honestly, it’s hard to be hopeful sometimes! It’s a practice we are trying to cultivate daily to keep us moving forward. Part of this practice is acknowledging the anger, grief, and despair that inevitably come up in moments like these.

The climate crisis is multifaceted; there is not one cause of the fires or their severity but rather many factors that lead to these conditions and exacerbate the effects. If you want to explore this further, here is a great instagram post providing guidance for how to frame climate disasters. Similarly to how there is no one cause, there is no one solution to this complex issue but rather a tapestry of solutions working together. We don’t believe that a circular economy is the one solution, nor is it enough to address the damage that has been done and will continue to happen. However, we believe that when combined with other approaches, it can be a thread that helps weave the tapestry of a better future.

Without Further Ado: THE TECHNICAL CYCLE

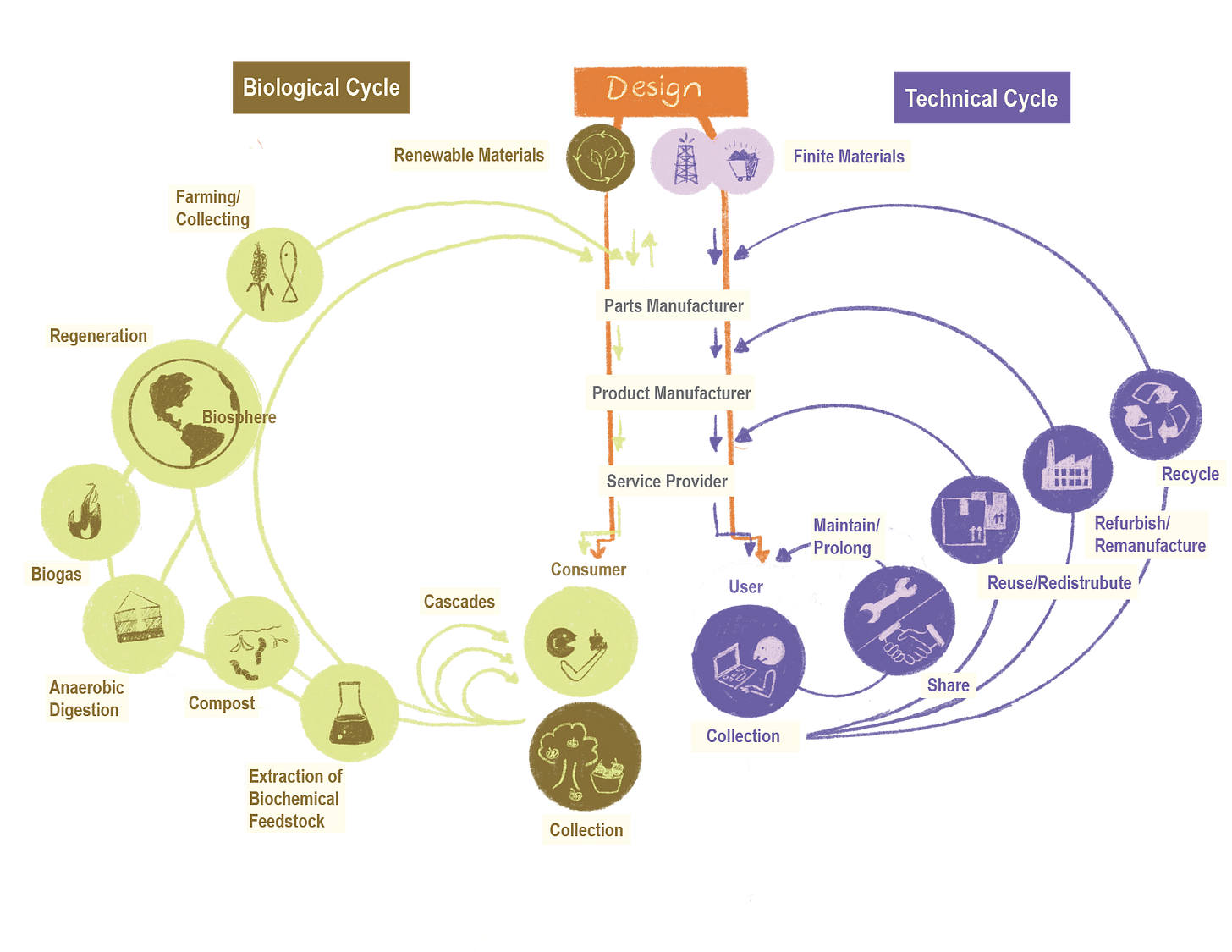

In our last post, we started to break down the butterfly diagram, focusing on the biological cycle. To refresh your memory, the butterfly diagram shows the two cycles of the Circular Economy:

The biological cycle: This is everything natural that can biodegrade such as cotton, food scraps, wood, and chipboard. These materials can re-enter the natural world after consumption without risk of pollution, as long as they are managed properly.

The technical cycle: This is anything that doesn’t biodegrade such as metals, rare-earth metals, plastics, polymers, and synthetic chemicals. Since these materials cannot degrade naturally, they constantly cycle through a system that recaptures their value.

Isn’t she gorgeous? Anyways, buckle up once again buttercup because this time, we are taking a journey through the technical cycle. As a quick reminder, the goal of a circular economy is to keep products at their highest value (meaning, being used as the product they are created for) and in circulation for as long as possible. The inner loops of the diagram, those closest to the user, are the ones that prolong the highest value because they keep products whole and should be prioritized.

Stage 1: Use

On this wing, the cycle begins with the user. The user uses the product (we know, a bit redundant) and tries to keep it in usable shape as long as they can. Products can cycle in this step for a looooong time, getting as much use as possible in their highest value state before moving on. There is much that can be done in this stage by the user to prolong a product's lifespan, including repair, mending, and sharing.

Ideally, the user is not alone in this effort, and companies and/or communities help by implementing sharing systems so that the product can get as many uses as possible throughout its lifetime. An example is power tools. Do you own a drill? If so, how many times have you used it this year? A domestic drill is typically only used for about 6-20 minutes in its lifetime, but with a sharing system like a tool library, a drill could live up to its full potential by being used many more times by community members in need. This way, a drill can be used 20+ times a year instead of once or twice and each person wouldn't have to buy a whole drill when what they really need is a hole.

Another example is a repair cafe, where community members gather and help each other repair small electronics, mend holes in clothing, kintsugi broken pottery, and come up with creative solutions for other products that need repair. Brooklyn Public Library hosted a series of repair cafes in 2022, and Grace was able to mend a beloved sweater!

Since we are designers, our ~hot take~ from the last issue still applies here (arguably even more strongly): We think the technical cycle really starts with making sure things are designed with durability, modularity, easy repair, and maintenance in mind. So much of the waste and excess consumption we encounter in a linear economy starts at the design stage. Too much of the responsibility to bear the weight of system change tends to be placed on the user, rather than manufacturers/designers, and we can see it here in this diagram!

Stage 2: Reuse/Redistribution

Once the product has reached the end of its usefulness for you but still has life left for someone else, it is collected to be redistributed or reused. For example, the biggest carpet tile company in the world, Interface, leases their carpet squares. This means that you pay for the service of having carpet but you don’t own the carpet itself. Let’s say you have carpet tiles in your office building but your office closes because everyone is working from home. Oh no! What do you do with the perfectly good carpet tiles? In a circular economy (or even this one if you’re using Interface) the carpet company picks them up, gives them a good clean, and takes the renewed tiles to a preschool that just opened so the kids can roll around on the floor comfortably.

In a linear economy, we tend to rely a little too much on the potential for an item to be reused by someone else to fuel our consumption. Take clothing, for example. Every spring we go through our closets and sort things into keep, donate, and trash piles, cleaning our closets out so that we can create space for new purchases. We feel good about sending our unwanted donated clothes to a thrift store where they can be loved by someone else - it’s better than in the trash! However, As Oliver Franklin-Wallis writes, “only between 10 and 30 percent of second-hand donations to charity shops are actually resold in stores. The rest disappears into a machine you don’t see: a vast sorting apparatus in which donated goods are graded and then resold on to commercial partners, often for export to the Global South.” Ideally in a circular economy, we are more selective with the products we consume in the first place so we don’t rely too heavily on their potential for reuse.

Stage 3: Refurbish/Remanufacture

There comes a point where after all that wear, products inevitably tear and require more than just a little cleaning to be usable. Instead of throwing them away, they can be repaired or components can be replaced either by an individual or by specialists to continue to be used. Taking our trusty carpets as an example, perhaps one of the kids in the preschool decides that cutting shapes into the carpet tile would be a fun art project. While we appreciate the creative spirit, this tile needs to be fixed to continue being used as carpet. The carpet company would come, collect the cut-up tiles, repair them, and replace them. In more dire cases, they might remanufacture products or their components which means breaking down and re-engineering the product until it is like new. This is a resource-intensive process and is more effectively done if products are designed to be modular and thus easily taken apart and remanufactured.

Remember in the last issue when we said these phases don’t have to happen in the order we present them in? This is one of those cases. The reuse, redistribution, refurbishing, and remanufacturing of a product can all happen in different orders. Ideally you cycle between them as many times as possible to prolong the life of a product before getting to the last step - recycling.

Stage 4: Recycling

In this stage, the product is fully broken down into its raw materials and reprocessed to create new, usable materials. Coming back to our carpet tiles, after they are used and repaired as many times as possible, they are taken apart and the components are recycled and used to make new carpet tiles. Recycling is truly the last resort in the circular economy and should be done only once all the other stages have been moved through. This concept is contrary to our current linear economy, which treats recycling as a primary solution to consumption in some cases, despite its dubious effectiveness (more on this later). Recycling requires a lot of intricate infrastructure to be effective, which does not currently exist at the level necessary. Circularity will require big investments at a city, state, and ideally nationwide level to create this infrastructure, although some towns are taking things into their own hands and creating circular recycling systems for themselves.

Whew, ok! That was a lot! We will probably never use the word “carpet tile” again.

Hopefully now you understand a bit more of the “how” behind the circular economy, but TL;DR:

Keep biological and technical materials separate throughout their life cycles

Do everything you can to keep products at their highest value for the longest time possible

Recycling is the last resort

The burden of system change is not on the consumer!!!!

We hope you enjoyed this issue of Full Circle! Stay tuned for our next issue where we will explore consumer culture in more depth, the origins of single-use products, and the behavioral shifts we may encounter as we move from thinking linearly to a circular mindset.

Is there anything that you found new or surprising? Anything you disagreed with? Anything you would like to know more about? As always, feel free to drop us a comment!

Until next time!

<3 Cas & Grace

Very nice post, clear and well explained!